Lost Histories of Bilingualism

Christine Sleeter • February 9, 2014

A week ago, while watching the Superbowl with friends, I saw Coca Cola’s now-famed ad E Pluribus Unum. At first, I was puzzled why I wasn’t following the lyrics to America the Beautiful, then realized they were being sung in multiple languages — English, Spanish, Keres (an indigenous American language), Tagalog, Hindi, Senegalese French and Hebrew. Regarding pluralism as normal, I appreciated what Coke was doing (even though I don’t appreciate sugary drinks), admired the artistry of the ad, then promptly forgot about it.

I was surprised a few days later to hear about the tremendous uproar it prompted. We have certainly lost our histories of bilingualism! On Coca Cola’s Facebook page, while there are far more likes than dislikes, the comments section includes things like the following:

- Disgraceful!

- Unpatriotic

- Speak English or go home

- No Coke for me

- De-Americanize America, divide and conquer

While I do not know those who are offended by the ad personally, I do know many people (most of whom are of European descent) who share their sentiment. Many us Euro-Americans assume our ancestors readily and willingly traded in the languages and cultures they brought in order to become American. For a huge number of us, however, this assumption is false. But since our own histories were suppressed in the process of erasing our ancestors’ languages, we aren’t aware of those histories. Let me share a bit of mine that I uncovered using family history research tools.

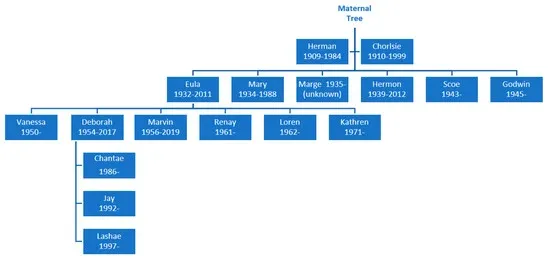

My father’s side of the family was of German descent. My German immigrant ancestors arrived to the U.S. between 1843 and 1868, most coming to Illinois but at least one to Pennsylvania. As nearly as I have been able to piece together, they left Germany primarily because of a combination of war as Prussia was expanding, poor crops leading to the possibility of famine, and to join other family members who preceded them. They helped to create and lived within what became bilingual, bicultural communities. In their case, the German church was an important institution that maintained bilingualism for about sixty years. How do I know that?

1. Visiting where my ancestors lived.

Browsing through Ancestry.com, I learned that in October of 1855, one of my German immigrant ancestors helped to found Zion Chapel (which had been a German Methodist church), in Boody, Illinois. So, on a trip to Illinois, I visited the church. There, I was able to read church records, including hand-written records from its early years. In so doing, I not only saw that its language had been German, I also learned the German origin of my name – Sleeter — which was Schlichter in church records. (Apparently church members had two sets of names: English names for records kept in English, and German names for records kept in German.) I was also able to read Zion Methodist Church centennial records, where I learned that Rev. Peter Hehner had been sent to Boody by the St. Louis Conference of the German Methodist Church in 1855; 18 German residents (including great-great grandfather Wilhelm Schlichter and great-great grandmother Amelia Farharenhorst’s father) established the church, initially in Wilhelm Schlichter’s home.

2. Digitized old newspaper articles.

While I do not have access to the German press from that era, English newspapers occasionally featured German church events. For example, an article in the Saturday Herald, describing the anniversary celebration of Zion Chapel’s Literary Society in August, 1887, noted that “some of the songs, and most of the other exercises were in German. Since the audience was made up of those who spoke both languages equally well all were alike enjoyed.”

3. Library and historical society research about specific churches.

Writing in 1923 about Zion Chapel in the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (vol. 16), N. M. Baker noted that its services were held continuously in German “until the late war [WW I] made the use of German unpopular” (p. 102). More about that below.

One of the other German immigrants in my family tree was a German Methodist Episcopal pastor. Once I found that out, I sought information about the denomination and the training of pastors. A little internet research revealed that German Methodist churches had been started in the U.S. in the 1830s, as a way of ministering to German immigrant communities. Dr. Wilhelm Nast, who has been called the father of the German Methodist Church, was a missionary to the U.S. who translated basic Methodist documents into German in the 1830s. Two seminaries were established to prepare German Methodist ministers: Nast Theological Seminary in Ohio, and Central Wesleyan College in Missouri. According to Rev. G. Davies, writing in the 1929 publication Journal and Year Book of the Illinois Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church (Wagoner Printing Co., p. 375), noted that my ancestor Rev. Ross continued his earlier education in Germany by attending Central Wesleyan College, located initially in Quincy Illinois. In 2006, O. E. Kriege described the program at Central Wesleyan College as producing “well equipped bilingual ministers” who are generally expected to do German services in the morning and English in the evening; and demand outstrips supply (in S. M. Jackson, editor, The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Vol VII. Kessinger Pub,, p. 367).

So what happened?

To investigate, I read newspapers published in Illinois during World War I. The quotes below are all from the Decatur Review.

In July, 1914, war erupted between Austria and Serbia, then Germany declared war on Russia, France, and Belgium in rapid succession. While the English-language press joined England in siding against Germany, German-Americans attempted to present Germany’s point of view while also reaffirming their own American patriotism. For example, Decatur lawyer Albert G. Webber wrote on August 11:

A German-American citizen in expressing his view upon the very unfortunate war situation in Europe is liable to be misunderstood and have his loyalty to the government of the United States questioned. First, let me say, I believe every thoughtful honest German-American citizen cannot help resenting every insinuation, that because of his sympathy for the German people, that he is betraying disloyalty to the United States. When the destiny of this government was trembling in the balance of uncertainty, no nationality furnished a larger percentage of valiant soldiers to maintain the union than was furnished by the German-American people.

After pointing out German-Americans’ active role supporting the Union during the Civil War, then distinguishing between the German Kaiser and ordinary German citizens who had no control over the Kaiser, Webber went on to situate the conflict within European resentments toward Germany.

Another German American, making much the same argument, pointed out a month later that “The German people are looked upon as foreigners, the English as ancestors.”

In 1915, Germany added England to its list of enemies, and sank the Lusitania, believing it was carrying munitions. By 1917, as Germany increased its submarine attacks against non-German ships, German-Americans worked to affirm their loyalty to the U.S., now downplaying their German roots. For example, a national convention the National German American Alliance passed resolutions “endorsing the action of President Wilson in severing diplomatic relations with Germany and pledging its loyalty to the United States.” The Alliance also lamented a growing backlash against German-Americans: “Our delegates felt that we have been greatly misunderstood and unjustly criticized during the war, but if it comes to a war with Germany, our actions will not be susceptible to any further misunderstanding, for we will back up our American government with our lives and our means.”

In August, 1917, former President Teddy Roosevelt announced that “some senators, congressmen, and newspaper editors” were “standing where the copperheads stood in the civil war.” He demanded “suppression of the German language press” and “deportation of ‘fifty-fifty Americans.’” A month later, the Post Office Department considered “exclusion from the mails of certain influential German language newspapers printed in various sections of the United States . . . as a part of the government’s determination to prevent circulation of anti-war propaganda.”

The governor of Iowa announced a plan to “stamp out disloyalty,” saying that he hoped to see “a sentiment created in our state so strong, so vigorous and so overpowering that no disturber or enemy sympathizer will dare to start his disturbance in any community in our state.” (Iowa shortly after that outlawed any use of the German language whatsoever.)

German-Americans, particularly those born in Germany, were targeted as spies in a German plot to colonize America, using the German press to give the Kaiser’s orders to Germans in America. In summer, 1918, newspapers noted to the internment of German-American citizens in Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, and the lynching of a German-American coal miner in Collinsville, Illinois:

- “Half a dozen German civilians interned at Hot Springs, NC are reported dead of typhoid fever and 165 ill as a result of drinking unfiltered water from French Broad river with the hope that their illness would prevent the war department from transferring them to the military prison camp at Fort Oglethorpe, GA.” (Aug. 14, 1918, p. 1)

- “Huns After Facts on Prager Lynching. That the lynching of Robert Paul Prager allegedly German spy April 5, last, will be made a matter of representation by the German government was indicated in a letter received by John Mellon, clerk of the circuit court. Requesting accurate information regarding the lynching.” (July 21, 1918, p. 23)

Reports in Decatur newspapers sketched assaults on the German language; here are a few from the Decatur Review:

- “Warn town to stop talking Hun. Lincoln, Neb., Aug 29 – Citizens of Harbine, Neb. yesterday rode by automobile to Plymouth, a neighboring town and placarded the place with notices demanding that the use of the German language in Plymouth be stopped.” (Aug 29, 1919, p. 1)

- “Mrs. Zua Hobson, patriotic Instructor of the W. R. C., ‘called down’ one of the Alhambra players at the chautauqua Saturday afternoon for using the German language in telling a story. He continued with his story and was branded as a German sympathizer by Mrs. Hobson, who searched tor him after the program with the intention of prosecuting him, but he could not be located.” (Aug 27, 1918, p. 6)

- “A communication was received from citizens of the west asking that the minister of a German church be requested to preach in English and that the songs be sung in English.” (June 15, 1919, p. 4)

- “Painters are engaged at the German church in Belleville in removing the yellow paint placed there a week ago by vandals. The building is to be repainted. The authorities are unable to find any trace of the parties who desecrated this house of worship.” (July 29, 1919, p. 9)

- “Singing of German opera in the German language is banned in New York until after the peace treaty is ratified.” (Oct. 28, 1919, p. 11)

The teaching of German in high school was suspended. When the superintendent of Decatur schools was asked in June, 1919, whether German might be restored after the war, he replied: “I suppose it will be put back sometime. But there will not be any hurry about it so far as I am concerned. The more I learn of the German conduct of this war the less I am in sympathy with things German.”

Methodist church publications concurred with the sentiment to ban German. Writing in The Christian Advocate, a weekly newspaper of the Methodist Church, Bishop Cooke proclaimed: “nothing separates humanity like diversity of tongues . . . let our preachers and people use only the English language . . . we should preserve the unity of the nation and foreign language is not the language of the young people of America.”

German was so thoroughly suppressed by the end of the war, and further with World War II, that not only was German-English bilingualism destroyed, but so too was historical memory that it had even existed. I invite readers to look into their own family histories, using research tools and frameworks available to them. We need to resurrect these suppressed histories and make them public, so that we do not continue to do to others the violence done against our own ancestors.

Christine Sleeter

I have changed the location of my blog. Please sign up for it here: https://christinesleeter.substack.com/about

Greetings to my newsletter and blog followers! I am shifting my blog and newsletter to Substack . There’s a lot going on these days. I intend to offer a monthly commentary on events related to education and racial justice, and my most recent work. You are probably aware of the January 29, 2025 White House Executive Order entitled “ Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling .” It claims in part that “innocent children are compelled to adopt identities as either victims or oppressors solely based on their skin color and other immutable characteristics.” This—whatever it means in practice—will be deemed illegal and enforced through the withdrawal of federal funds to schools, teacher preparation programs, and any other education institutions that receive federal funds. At the same time, the White House proposes to resurrect the 1776 Commission with the charge of promoting a patriotic education. There is much that can be said about the vagueness of the executive order and what it might mean. More on that vagueness in a later post. For now, so far Ethnic Studies (now required by several states and many additional school districts) is not exactly in the crosshairs of this executive order. But it could land there. Therefore, all of us should be familiar with the research that supports the academic value of Ethnic Studies. Although ethnic studies was not designed specifically to close racial achievement gaps, it has a track record of doing exactly that. In two studies of San Francisco Unified School District’s ninth-grade ethnic studies program, Stanford researchers Dee and Penner , and Bonilla, Dee, and Penner found the course to improve students’ grade point average, school attendance, and graduation. In other words, a course taken in ninth grade improved the GPA of students in other courses, and also their rate of high school graduation. Impressive! Similarly, University of Arizona researchers Cabrera, Milam, Jaquette, and Marx found that participation in Tucson’s Mexican American Studies program raised students’ achievement on the state’s reading, writing, and math achievement tests and virtually closed racial achievement gaps; their study is published in the American Educational Research Journal. Several other studies have also documented gains in the achievement of K-12 students of color taking ethnic studies courses, but the studies described above are the largest in scale and strongest methodologically. Two additional studies have found that majoring in ethnic studies at the university level benefits students of color academically. San Francisco State University researchers Sueyoshi and Sujitparapitaya found that students who major in ethnic studies graduate within six years at a much higher rate (92%) than students in other majors, and that students in other majors who take at least one ethnic studies course boost their graduation rates compared to students who do not. At the University of Louisville, researcher Tomarra A. Adams found that Black students who major in Pan-African Studies have a higher graduation rate than Black students who major in something else. The consistently positive impact of Ethnic studies on the academic achievement of students of color is not due to ethnic studies watering down the curriculum (let alone compelling students to adopt identities as victims or oppressors!). Indeed, students usually describe it as more academically challenging than their other courses. By offering a relevant curriculum that speaks to issues of concern to their lives and communities, ethnic studies engages the knowledge students bring to the classroom, allowing them to draw from and recognize their own expertise. The classes offer an environment where relevant issues related to race and ethnicity can be addressed openly. Further, as students of color come to see education as relevant to addressing problems and needs in their communities, and themselves as academically capable, they gain confidence to thrive in school more generally. So if you hear anyone attempting to argue that ethnic studies violates the Executive Order, you can tell them that, on the contrary, ethnic studies empowers students, and particularly students of color. See you on Substack next month!

How did the tobacco industry sow doubt about the research-documented link between smoking and lung cancer? Why are we still debating the link between human activity and global warming? In a recent conversation, a colleague and I began to explore connections between the anti-Critical Race Theory movement, and science denial. (For an excellent examination of the latter, see Science Denial by Gale Sinatra and Barbara A. Hofer.) I was directed to the book Merchants of Doubt (by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway), which lays out the playbook created by the tobacco industry, and has been applied since then to sowing doubts about other science-documented problems. Essentially, the playbook is this: When research evidence begins to undercut an industry or a way of life that some people are benefiting from greatly, the industry or benefiting group begins to seek out credible spokespeople who will cast doubt on what has otherwise become a consensus. To be credible, the doubters need to be scientists themselves, or otherwise members of the community that has been marshaling the unwelcome evidence. The doubters then gain access to the media, who report the doubts and cast the issue as still open to debate, even if it isn’t. They do this by pointing to exceptions and contrary evidence, exploiting claims of causality, and using hot button terms. Most journalists aren’t experts, but journalists relish having a good story. Journalists strive to present both sides, even if there isn’t really another side that has much evidence or credibility. The public, unaware of the research, learns about the issue from how the media report it—as a debatable issue with many unresolved questions. Much the same playbook being used to generate fear and backlash as white people lose control over a nation whose population continues to diversify. The strength of a multiracial coalition of voters put an African American man into the White House twice. By the mid 2040s, the nation is predicted to be majority “minority.” How will white people fare, especially if rules and norms that are biased in favor of whites are changed? Behold the disinformation campaign that has resulted over the past three years: When research evidence as well as narratives by people of color undercut the claim that systemic racism does not exist, many white people begin to seek out spokespeople who will cast doubt on its existence. To be credible, those spokespeople need to be people of color themselves, and/or people who have studied racial issues. The doubters gain accessed to the media, who report the doubts and cast the issue as still open to debate, even after those who study race agree that the existence of systemic racism is clear. They do this by pointing to exceptions (people of color who made it on their own) and contrary evidence (e.g., DEI training that went badly), and exploiting claims of causality, and using hot button terms. Most journalists aren’t experts, but journalists relish having a good story. Journalists strive to present both sides, even if there isn’t really another side that has much evidence or credibility. The public, unaware of the research, learns about the issue from how the media report it—as a debatable issue with many unresolved questions. In September of 2020, when Chris Rufo was invited to appear on Tucker Carlson’s Fox news show, this playbook sprang into action for the field of education. Here’s what happened: Research evidence as well as narratives by people of color document that systemic racism exists (the books and articles reporting research are voluminous). In education, systemic racism includes factors like tracking, school segregation, Euro-centric curriculum, an overwhelmingly white teaching force, discipline policies, etc. (Again, voluminous research publications for each of these; my work has synthesized research related to curriculum; see for example What the Research Says about Ethnic Studies ). Many white people who worry that addressing these factors will harm white children seek out spokespeople who will cast doubt on the existence of systemic racism in education. The doubters gain accessed to the media, who report the doubts and cast the existence of racism as still open to debate. They do this by pointing to exceptions (students of color who excelled in traditional schools, particularly Asian students) and contrary evidence (e.g., anti-racist teaching that went badly), and by using hot button terms (critical race theory; pornography). The right has used this issue to mobilize white parents to resist or overturn equity-oriented school policies, and to vote for MAGA candidates. What should be done? In agreement with authors of the books mentioned above, I believe that those of us in the research community need to give much more attention to synthesizing what the research says in terms lay people can understand, and put this work in places where they will encounter it. I gave a lecture for a lay audience in my community recently, which was very well received. Attendees had heard various things about “critical race theory” in the news, but didn’t know what to make of it until I clarified what critical race theory is, what systemic racism is, and how this controversy has been manufactured. Research alone will not change everyone. Race and racism evoke strong emotions; many people hold opinions they are strongly wedded to. But more communication about what the research says for a broad audience will help.

Posted earlier on the Teachers College Press website On November 16, 2022, PEN America released a report that found Missouri schools to have banned nearly 300 books since August, when SB 775, a new law that criminalizes “explicit sexual material,” went into effect. Under that law, providing such material to students in class is a misdemeanor, punishable by up to one year in jail and a $2000 fine. Although the law allows for some exceptions directly related to education, many educators find it intimidating. To be on the safe side, 11 school districts pulled almost 300 books from their shelves. These include books that go far beyond the letter of the law, such as Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale , Gabriella Di Cagno’s Michaelangelo: Master of the Italian Renaissance , Sean Murphy’s Batman: White Knight , and Don Nardo’s Life in a Nazi Concentration Camp . Some of the recent surge of censorship aims to omit historical accounts that present the US in an unfavorable light, and some aims to sustain the marginalization of people of color and members of the LGBTQ community. In spring of 2022, two reports investigating book banning were released, one by PEN America and the other by the American Library Association. They found, respectively, 1,145 and 1,597 books had been challenged or removed from shelves during 2021, far more than in previous years. As Natanson noted, “Most titles targeted in 2021 were written by or about LGBTQ or Black individuals.” The most challenged book that year was Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer, a memoir about what it means to be nonbinary. Other books on the most-challenged list include Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give and Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. Even biographies about famous people of color, including Ruby Bridges, Duke Ellington, Martin Luther King, Jr., Cesar Chavez, and Sonia Sotomayor have been banned. In September of 2022, PEN America released an update to their spring report, and found that the number of titles banned had increased to 2,532. They also found that in the 32 states with book bans, Texas led the nation, followed by Florida, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee. Forty-nine percent of the banned material was aimed at young adult readers (students in high school), but also included hundreds of books aimed at younger readers. There is a long history of school book censorship in the United States, which occurs mainly in response to movements that challenge social injustices based on race, gender, and sometimes class. During the first half of the 19th century, books about the enslavement of people were seen as dangerous, especially in the South. It was not only illegal to teach enslaved people to read, but by the 1850s, multiple states had outlawed expressing anti-slavery views. In 1873, in an effort to push back on women’s activism, Congress passed the Comstock Act, outlawing possession (and mailing) of “obscene” or “immoral” texts—namely, texts about sexuality and birth control. During the first half of the twentieth century, the United Daughters of the Confederacy pushed to ban school textbooks that were not sympathetic to the South’s loss in the Civil War. During the late 1940s, several large corporations succeeded in banishing Harold Rugg’s social studies textbooks that openly criticized capitalism. Ten years later, McCarthy-era censors challenged books they deemed sympathetic to Communism or socialism, including Huckleberry Finn , The Catcher in the Rye , and To Kill a Mockingbird . So, book censorship has a long history. Although many might assume that it reflects parents’ concerns, PEN America identified strategic advocacy organizations—73% of which had been formed as recently as 2021—as the main sources of agitation. In Critical Race Theory and its Critics , we delve into today’s culture wars in schools, situating them within a history of right-wing pushback against efforts to expand who counts as a full American citizen, and to address racism through education. We see the flurry of book banning and state legislation banning “Critical Race Theory” as a series of policy distraction tactics or contrived crises designed to distract citizens from real, pressing problems. Policy distraction diverts attention from pressing social issues such as the rapidly escalating wealth gap, and from conservative policy initiatives many people may not support, such as shrinking or eliminating social programs they are using. The efforts are highly strategic: as Pollock and colleagues have shown , anti-CRT provocation by media, politicians, and pundits has been concentrated in predominantly White contexts where there has been an increase in diversity of the student population. The rhetoric provokes fears that an equitable curriculum will make White children feel guilty for being who they are, and will indoctrinate cis-gender heterosexual children to engage in “ controversial lifestyles .” It is no accident that today’s anti-CRT efforts to distract the public increased immediately before elections. In our book, we also describe the role of social media in accomplishing the goals of those who aim to thwart equitable efforts in education. That is, by leveraging the reach of social media, politicians and pundits provide language and material for others to use in spreading fears about equity in schools. This was consistent with PEN America’s findings that book bans operate predominantly through spreading fear and misinformation via social media. What to do? Lawsuits are beginning to be filed, and they have precedent. In 1982, in the case Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico , a group of students in New York sued a school board for removing books by authors like Kurt Vonnegut and Langston Hughes—books the board saw as “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic, and just plain filthy.” The Supreme Court, in upholding students’ First Amendment rights, wrote: “Local school boards may not remove books from school libraries simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books.” By Spring 2022, educators in three states, working with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and other advocacy organizations, had filed four lawsuits. In October 2021, the first was filed against the State of Oklahoma by the American Civil Liberties Union, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, and other advocacy groups. The lawsuit claims that Oklahoma’s HB 1775 violates the First Amendment and denies students the access to learning their history. In December 2021, teachers and parents in New Hampshire, working with the American Federation of Teachers, filed suit. The suit “alleges the law is at odds with the state’s Constitution, prevents teachers from meeting certain education standards and violates their constitutional rights to free speech and due process.” A week later, two educators, working with the ACLU, the NEA, GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders (GLAD), and the Disability Rights Center–NH also filed suit against the same law for the same reasons. In April 2022, three teachers, a student, and a consultant who provides diversity and equity training filed suit against Florida Governor DeSantis’ Stop WOKE Act (HB 7). The plaintiffs are claiming First and 14th Amendment violations. The Southern Poverty Law Center filed an amicus brief, claiming that the new law “has already interfered with the ability of students to obtain true and accurate information about the history of their society.” In all three states, educators found support by working with the teachers union and the ACLU. These cases illustrate steps educators can take to challenge gag order legislation .

In the context of anti-CRT efforts, the right’s core narrative, which relies on fear and anger, manipulates the public into believing equitable education efforts are designed to harm White students, and that science-based policies conflict with common sense. Many parents and legislators had not thought deeply about these issues until they became the focus of controversy, and had never heard of Critical Race Theory until the right transformed it from an academic theory into a scary caricature. We now see predominantly White parent groups and state legislators organizing to oppose curricula and pedagogy that research finds beneficial to all students, particularly students of color. Many voters are simply perplexed, but hear the right’s narrative more loudly than they hear an alternative. Francesca López and I are in the final stages of completing a book, Critical Race Theory and its Critics (Teachers College Press), that will be available for purchase this coming spring. In that book, we examine right-wing messaging strategies and how to counter them. For example, in April, 2022, conservative blogger Christopher Rufo tweeted: The teachers unions shut down schools for more than a year, endorsed critical race theory at their convention, masked children against the evidence, and trapped families in failing districts. Now they're looking to shift the blame. But it won't work. Parents have seen the truth. This tweet follows a pattern that is common on the right. It frames Critical Race Theory and mask mandates as the problem, teachers and teachers’ unions as the villain, and families who fight against these things (who are mainly White and affluent) as the solution. Based on his excellent analysis of messaging, in his book Merge Left , Ian Haney López (2019) explained: "The Right’s core narrative urges voters to fear and resent people of color, to distrust government, and to trust the marketplace. The Left can respond by urging people to join together across racial lines, to distrust greedy elites sowing division, and to demand that government work for everyone " (p. 174). Similarly, the organization Words that Win aims to educate the public about strategic messaging. In a series of short articles, Words that Win summarizes key strategies that are imperative to successful coalition building. Three key components of a successful message include naming a shared value, calling out the villain, and ending with a shared vision. So, Rufo’s tweet can be countered with a message that goes something like this: No matter where they are from or what color they are, families want high quality education that their children can relate to, provided in schools that are safe to attend. These are measures that the teachers’ unions support. But today, a few political pundits and legislators are opposing inclusive curricula and public health safety measures in schools. By standing with teachers, we can ensure that all children can learn in classrooms that reflect people like themselves, and that they will not get sick in the process. Ian Haney López and his colleagues conducted extensive research to determine what kind of messages were most likely to persuade voters, particularly those in the middle. In a racially and ethnically diverse society, is it best to downplay our diversity, or to name it explicitly? Specifically, Lopez and his team wanted to know whether diverse coalitions can be built to work for economic justice initiatives, by naming our differences. He refers to such messaging as “race-class” messaging. He and his team found that “race-class messages were more convincing than colorblind economic populism” (p. 175). He points out that voters in the middle “hear racial fear messages everyday,” but find messaging that explicitly connects people across racial and ethnic lines to be more convincing. What all of this says to me is that those of us working to make social institutions such as schools work well and equitably for everyone can win public support when we frame value messages in explicitly inclusive ways (ways in which most readers can see themselves), name “villains” directly, and propose inclusive solutions that call on government to serve us all. You will see more discussion of these issues in our book, Critical Race Theory and its Critics , which will be available in spring, 2023.

In most states of the U.S., educational "gag order" bills have been introduced, and in fifteen states, they have been passed and signed into law . These laws are having a chilling effect on teachers' attempts to teach U.S. history honestly and to address contemporary issues involving race and gender in the classroom. But in Florida, two educators—Dilys Schoorman and Rose Gatens—have figured out how to upend gag order legislation and use it to support teaching from multicultural perspectives. Gag order legislation is often vague. That vagueness, as well as media spin regarding what any given legislation or proposed legislation implies, instills fear in teachers who aren’t sure exactly what they might be fired for. Gag order legislation also generally presumes a White and heterosexual point of view, attempting to ban concepts or practices that are uncomfortable for White people, but the absence of which may be uncomfortable for people of color and/or LGBTQ people. In addition, such legislation is often based on one-dimensional views or assumptions about what happens in schools, in the process banning practices that don’t actually happen or practices writers of the legislation did not intend. Let’s look at Florida’s House Bill 7, the Individual Freedom Act. HB7. This bill: Provides that subjecting individuals to specified concepts under certain circumstances constitutes discrimination based on race, color, sex, or national origin; revising requirements for required instruction on the history of African Americans; requiring the department to prepare and offer certain standards and curriculum; authorizing the department to seek input from a specified organization for certain purposes; prohibits instructional materials reviewers from recommending instructional materials that contain any matter that contradicts certain principles; requires DOE to review school district professional development systems for compliance with certain provisions of law. How did Dilys and Rose reframe the bill? Below are examples from their text, which you can download here.

One of my former doctoral students, William Watson, is in the process of publishing Twelve Steps for White America . This is a book designed to help White people work through layers of racism in order to become allies in work for racial justice. The book and its accompanying workbook draws on the twelve steps that are presented in Alcoholics Anonymous, since they function as a useful set of problem-solving principles for the human condition. The book itself weaves together story, factual information, and reflection tools. The workbook involves readers more specifically in applying tools and insights from each of the twelve steps to their own lives. Both are organized around three parts. Part I, Confronting the Truth, engages readers in various forms of reflection that focus on the gap between the ideals of a democratic society, and the realities, particularly for people of color. Part II, Reconciliation, engages readers in recognizing whiteness-affiliated rigged advantages and learning to seek ways to relinquish those advantages. Part III, Renewal, engages readers in ongoing reflection and spiritual strengthening that will enable White people to stay in the work for racial justice for the long haul. It is an honor for me that my work on Critical Family History is part of this book. It is nested within Chapter Four, which guides readers in drilling down into their own family histories in order to identify rigged advantages and how these have played out in the past to structure one's life in the present. With William Watson's permission, I am posting the section of the workbook that deals with Critical Family History here, for your use.

State laws taking aim at Critical Race Theory and anti-racist education are making many teachers, teacher educators, and other university faculty wary about teaching students about structural racism. Chalkbeat has tracked efforts in 28 states to restrict education on racism, bias, the contributions of specific racial or ethnic groups to U.S. history, or related topics. But it has also efforts in 15 states to expand education on racism, bias, the contributions of specific racial or ethnic groups to U.S. history, or related topics. I'm grateful to be living in one of those 15 states. But if you live in one of the states that restricts what can be taught but you are committed to teaching the truth, what do you do? Critical family history can provide a way around restrictions on content. Family history has become a popular pastime that few would regard as subversive. Yet, digging into one’s own family history often reveals structural racism at work. After all, everyone participates in racism in one form or another. The trick is not so much one of finding examples, but rather of recognizing them and using them to piece together a larger picture of how racism (and classism and sexism) work. Here are some examples, some from my work and some from the work of others. When seeking information about a great-great-grandmother, one of my sisters tried googling her name. What she found was an article published in the Sacrament Bee in 1882 (the article is no longer freely available online) about an organization our ancestor was helping to found, called The Woman's Protective League. It was dedicated to eradicating the employment of Chinese people in San Francisco, and particularly Chinese workers in white families. The document raises so many questions! Why was this happening during the same year Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act? Why did our ancestor, a white immigrant from Switzerland, become involved in trying to expel other immigrants? What additional organizations, city ordinances, state laws, and so forth were aimed at driving out the Chinese? What responsibility do the descendants of this ancestor have today to confront and deal with consequences of our ancestor's actions? Googling another ancestor, I found evidence of another set of great grandparents acquiring land in Colorado through homesteading, and building up wealth from selling that land, to reinvest in buying up and then selling additional land. Before finding that evidence, although I had traced the movements of these ancestors, I wasn't sure how they had acquired their wealth. Finding that piece of evidence gave rise to other questions, the big one for me being: What do I do with inherited wealth, knowing its roots in the dispossession of Ute people? Are there implications for other descendants of homesteaders? Grappling with these questions led to my novel The Inheritance . Mica Pollock looked into how her European ancestors became U.S. citizens, after noticing that her students seemed to assume that the same rules for becoming a citizen had always been in place. She found that he was treated as a citizen before actually becoming one, and that citizenship was granted easily to white people at that time. Her study of her own family history raises important questions about how people become citizens, what the rules have been during different decades of history, who could and could not become a citizen, and how those rules have been applied to which groups. Newman and Gichiru used oral histories with six women in three generations of the African American Newman family to paint a portrait of how they navigated the structural racism embedded in schools they attended. They contextualized the interviews with other data sources such as newspaper articles and census records. Racism spills out of the stories the women told in the interview process, enabling the authors to elaborate on what structural violence looks like and how it works, from African American perspectives. Mokuria, Williams, and Page describe the learning that occurred when an African American student (article co-author Williams), in delving into her family history, discovered the reality that many enslaved women, including one of her ancestors, were forced to become concubines -- in other words, they were raped. The student chose to present her findings to the class, which was mostly white. For the student and the class, the learning experience was transformative.

These are examples of insights that can surface when people dig into their family histories. Teachers, however, need to be prepared for the tendency of white students to re-inscribe triumphal stories they likely learned about immigrant ancestors who arrived with nothing and made good. Without denying their hard work, it is possible to encourage students to look into (or look under) what may be forgotten, hidden, or buried. For example, for a long time I assumed that none of my ancestors had been slave holders because I had not heard about it and slavery did not immediately jump out as I did family history research. But when I specifically asked myself that question, I discovered that yes, indeed, a great-great-great grandfather had owned a family before the Civil War. That discovery led to my novel Family History in Black and White . You don't have to invent how to teach family history in a way that unearths structural racism. Others have already been doing so, and some are posting their work on the internet or writing about it. For example, Susan Thorne shares her course Reckoning with Inequality Via Critical Family History , which she taught at Duke University in Summer, 2021. Jennifer Mueller has been teaching critical family history courses in sociology, as a way to examine inter-generational transfer of wealth, for many years. As she explains in her 2013 article in Teaching Sociology — "Tracing family, teaching race: Critical race pedagogy in the millennial sociology classroom"—she specifically asks her students to look into questions such as: "Is there a family history connected to slavery? Did anyone in previous generations inherit property, money, or businesses? Did parents or grandparents receive down payment help for purchasing a home or assistance with college? Did the family take advantage of formal programs that would facilitate wealth/capital acquisition, like the Homestead Act or the GI Bill? Did anyone use social networks to get jobs, secure loans, open businesses?" (p. 175). She also works to create a collaborative climate in her classroom in which "we are all in this together" so that students help each other and support each other as they deal with difficult information. Of course, you may need to remove the term "critical" from any course title or description. But looking into family history with a critical eye for what may be hidden or buried can be an excellent tool to unearth and examine issues that have been otherwise banned.